On the Immortality of Microsoft Word

And why tech people refuse to accept it

Lawyers and legal tech procurers often feel that vendors don’t ‘get it.’ They don’t understand what lawyers need and they build solutions for problems that lawyers don’t have. A tsunami of venture capital in the space has only amplified this dynamic. If you’ve spent time in r/legaltech in recent months, you’re surely aware of the shared frustration by both lawyers and legal tech procurers that this new crop of legal AI companies have over-promised and under-delivered.

Why is it easier for tech people to build machines that emulate human intelligence than it is for them to build software for lawyers that delivers value? As a software engineer who has spent the past five years working in legal tech, I have observed several patterns in products that miss the mark and in my own thinking that I believe explain the disconnect between lawyers and legal tech vendors.

My conclusion is that coders misunderstand legal workflows and that their misunderstanding is upstream of many mistakes in legal tech.

Of all the mistakes this misunderstanding produces, one stands above the rest—the desire to replace Microsoft Word.

Microsoft Word can never be replaced. OpenAI could build superintelligence surpassing human cognition in every conceivable dimension, rendering all human labor obsolete, and Microsoft Word will survive. Future contracts defining the land rights to distant galaxies will undoubtedly be drafted in Microsoft Word.

Microsoft Word is immortal.

Why?

Legal systems around the world run on it. Microsoft Word is the only word processor on the market that meets lawyer’s technical requirements. Furthermore, its file format, docx, is the network protocol that underpins all legal agreements in society. Replacing Microsoft Word is untenable and attempts to do so deeply misunderstand the role that it plays in lawyers’ workflows.

The origin of this misunderstanding can be traced to a common myth shared by coders — “The Fall of Legal Tech.”

Legal tech’s original sin

Throughout history, ancient cultures across the world developed myths about the creation and fall of mankind that mirror one another. So too do coders, drawing from the collective unconscious of the coder hive-mind, invent the myth of “The Fall of Legal Tech”. They mistakenly conclude that Microsoft Word is legal tech’s original sin and only its replacement will lead lawyers to salvation.

They have a variety of ideas of what form its successor will take. Some imagine it’s Google Docs. Others believe it will be their product’s proprietary rich text editor. The coders most committed to the ideals of technical elegance, however, propose that Markdown, a computer language for encoding formatted text, shall take its place.

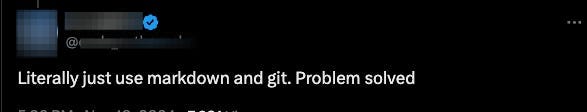

Markdown is ubiquitous amongst coders. It allows them to encode document formatting in “plaintext”. Special characters encode its text so that applications can render it with visual formatting. For example, to indicate that text should be italicized, Markdown wraps it in asterisks. E.g. *This text will be italic* -> this text will be italic.

Below is an example of a simple Markdown document with its written form on the left and its rendered form on the right.

Why do coders want lawyers to use Markdown instead of Microsoft Word? Because Markdown is compatible with git, the version control system that structures their workflow. If lawyers could use git-like version control, so many problems in the legal workflow could be solved. It’s why we’ve spent years building such a system for lawyers. Let’s get into why Markdown is not legal tech’s savior.

Formatting

Markdown doesn’t work because of formatting. “But Markdown supports formatting!” the coder cries. That is, in fact, its whole point — the raison d’etre of Markdown is to encode formatting in text. Isn’t that enough?

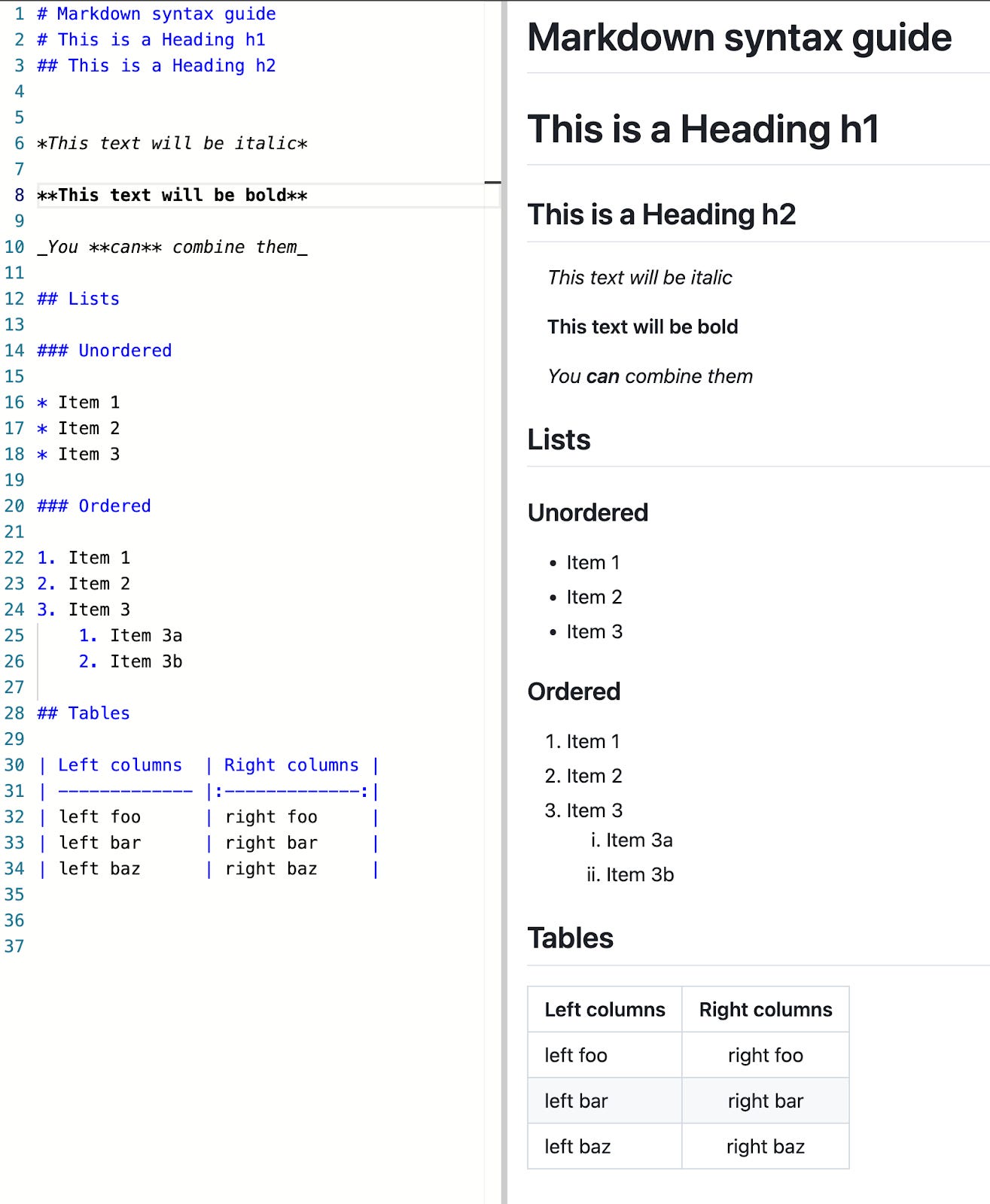

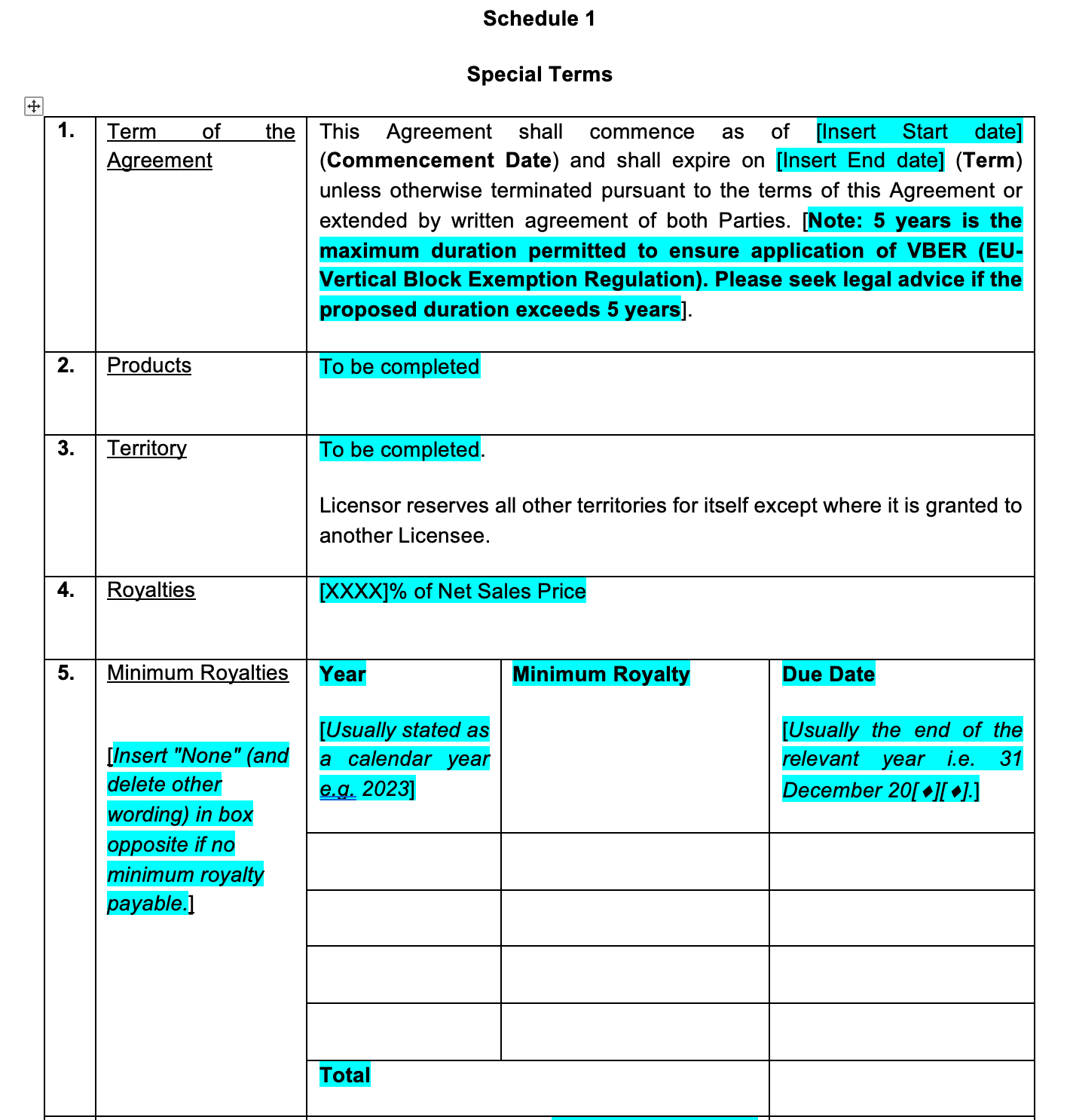

Well yes, Markdown supports certain formatting. It supports bold, italics, numbered lists, ordered lists, headings, tables, etc. But what happens when a lawyer wants to style their headings in “small caps”, as my lawyer cofounder Kevin insists? Okay, perhaps we can add that formatting option to Markdown as well. But what happens when a law firm needs their documents to use multi-level decimal clause numbering like in the below screenshot?

Or how about when we need to specify the precise width of a column in a table that differs from the width of the other columns or split a particular cell to contain additional rows that other cells don’t?

Sure, we could theoretically encode that rule too and all other formatting rules until we’ve accounted for all of the formatting possibilities that lawyers actively use. By that point, however, we will have effectively recreated Microsoft Word but in a format that is significantly more challenging to use.

“But style doesn’t matter!”

Surely, many coders who have read up until this point are thinking the following objection: why do lawyers need all of those extra formatting options? The styling properties of lists don’t matter – all that matters is the information they convey.

Herein lies a cultural difference between the fields of coding and lawyering. For coders, visual aesthetics don’t matter. For lawyers, they are a technical requirement. While this difference may seem arbitrary on the surface, it is downstream of a critical technical difference between the two fields. Machines interpret the work of coders. Human institutions interpret the work of lawyers.

Concretely, visual presentation doesn’t matter for code beyond basic legibility because a machine ultimately executes the code. Courts interpret legal contracts, by contrast, and courts often have specific formatting guidelines that Markdown and other non-Word alternatives do not satisfy.

For example: federal appellate courts require all “briefs, appendices, and other papers” to adhere to the following formatting conventions:

14-point proportional typeface is mandatory, and Markdown cannot specify font size or font family.

Double-spacing for all text, with narrow exceptions for block quotes and headings. Markdown has no concept of line-spacing rules.

Precise margin requirements (at least one-inch on all sides) and 8.5×11-inch page size, which Markdown cannot express.

Roman-numeral and Arabic page-numbering schemes, footers, and separate formatting for cover pages, none of which Markdown can natively encode.

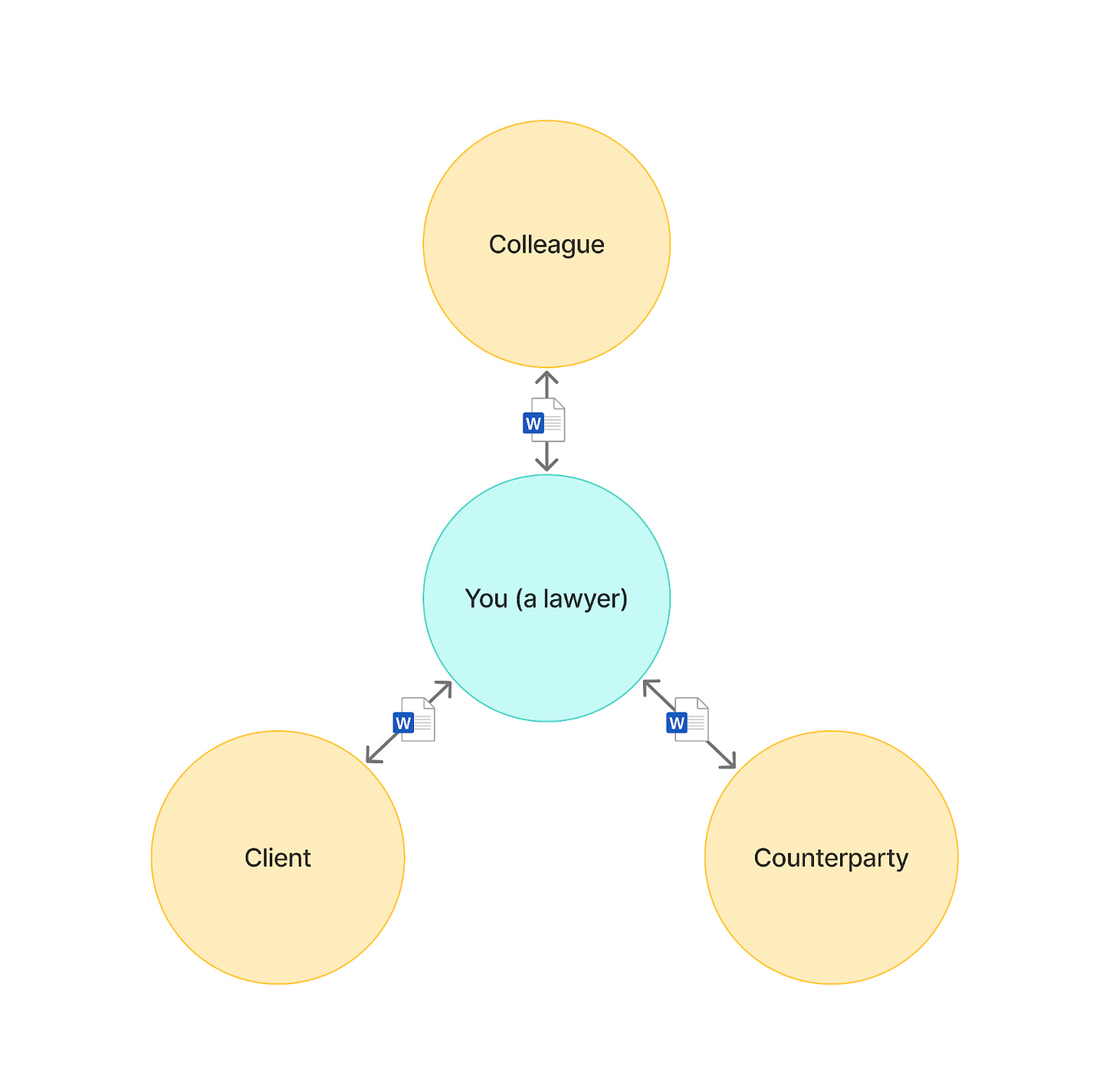

Additionally, a well-formatted document is a symbol of a lawyer’s professionalism. Courts aren’t the only readers of legal documents. Clients, counterparties, colleagues, all read a lawyer’s documents as well. The style of their work product reflects the lawyer’s professionalism — the medium is the message.

Docx is a protocol, not a filetype

Beyond styling considerations, another structural consideration of the legal workflow prevents Microsoft Word’s defenestration — the legal system is decentralized.

If a coder wants to adopt a new file format for their internal documentation or new programming language, they can rewrite the relevant parts of their codebase. They are able to do so by virtue of having autonomy over the system they operate. While this becomes more complex in an engineering organization, the principle remains that the organization has the necessary autonomy to change its systems.

In the legal world, a lawyer cannot simply choose to adopt a new file format. This is because all existing legal precedent is in the old format. Docx encodes virtually every outstanding legal commitment for every person and corporation in our society. A lawyer could choose to adopt a new file format, but the system will break when they need to redline it against precedent.

Additionally, every colleague, counterparty, outside-counsel, and client a lawyer ever works with uses docx. To introduce a new format into this ecosystem would introduce friction into every single interaction. If a lawyer sends a contract in Markdown, the counterparty cannot redline it. If they send a link to a proprietary cloud editor, the client cannot file it in their internal document management system. In the legal industry, asking a client to learn a new tool to accommodate your workflow is a non-starter.

An appropriate technical analogy for docx is a network protocol. A coder cannot just decide to stop serving their web application over HTTP. Doing so would disconnect their application from the web and render it useless. The same goes for lawyers vis-a-vis docx. Docx is a protocol for defining legal commitments across a decentralized network of legal entities. Opting out of that system is not viable if the lawyer wants to stay in business.

This dynamic explains why legal tech products fail when they force lawyers to use a document editor outside of Microsoft Word. They attempt to introduce a walled-garden platform in an industry that runs on an open protocol. When a tech product requires both sides of a transaction to be on the same platform to collaborate effectively, it breaks the protocol. Until a startup can convince the entire global legal market to switch software simultaneously, .docx remains the only viable packet for transferring legal data.

How to innovate in legal tech

Accepting Microsoft Word’s primacy in the legal workflow is not technological defeatism. Progress shall continue! But impactful innovation in legal tech requires contending with Microsoft Word. Moreover, it requires cultivating a deep understanding of the practice of law beyond a surface-level recognition of the similarities between coders and lawyers.

At Version Story, this understanding originates from our lawyer/coder CEO, Kevin O’Connell. His experience in both fields has given us a unique vantage point in the industry, allowing us to understand the legal workflow as it exists while imagining what it can become. That vantage point has been critical in building a version control and redlining product that lawyers love.

If more coders and technologists learn the way lawyers actually work, we can expect a future with innovative legal technology that truly adds value. Not revolutions, not ChatGPT wrappers promising to remove lawyering from the practice of law, but meaningful step-changes that help lawyers to spend more time exercising legal judgment and less time wrangling documents.

Legal tech never fell. It doesn’t need full-stop salvation. It needs good products built by people who understand lawyers.

False. Legal systems use PDF for documents. For editing anything can be used. From MS Office to cloud systems. Formats? docx or odt. It doen't matter. But final documents are always PDFs and Digitally Signed PDFs. And yes, I work with laywers and at a big legal system on gov. Sorry, but you know nothing, Jon Snow.

There was Wordperfect. Between MS foisting it on everyone and missteps, writing world has regressed