The future of Legal Tech will be built by lawyers

And what secure vibe-coding infrastructure for law firms could look like

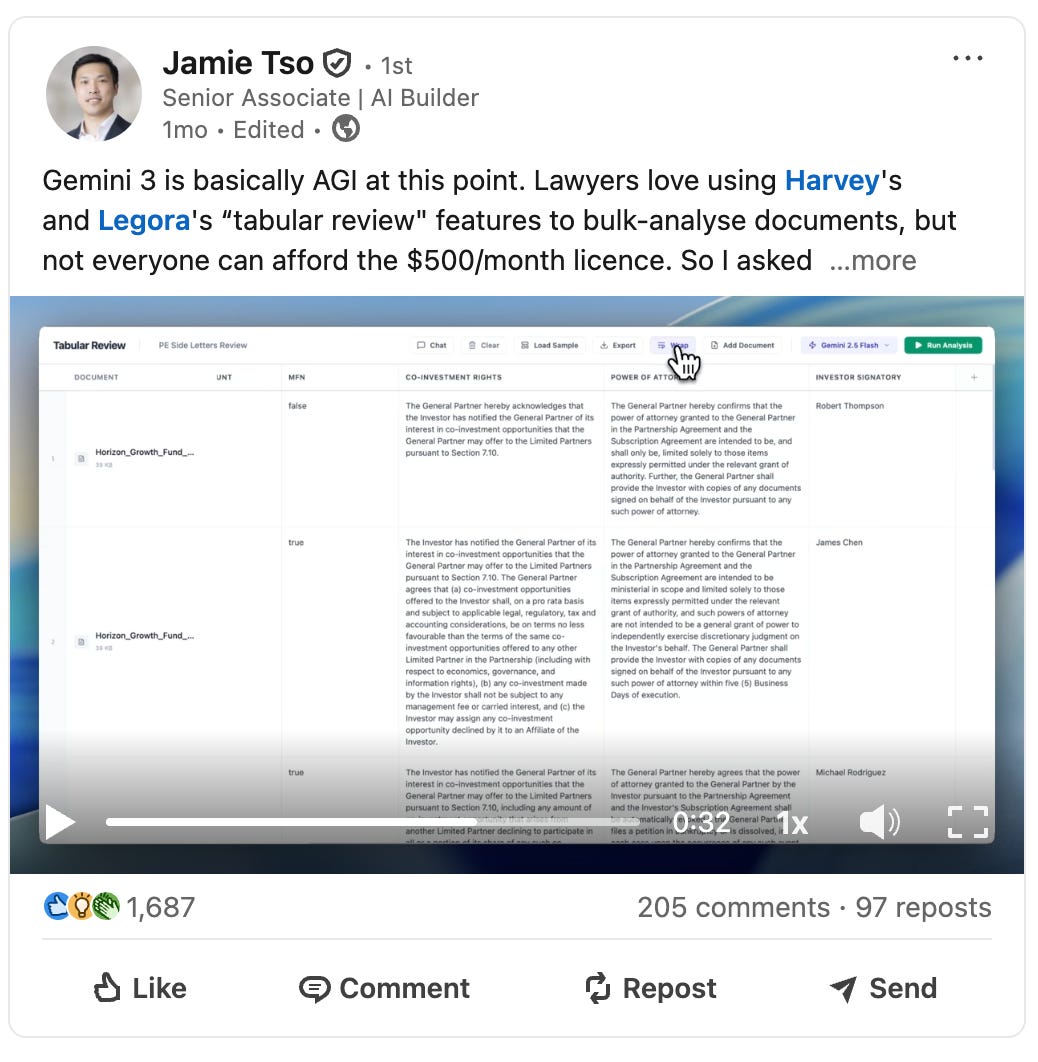

One month ago, an associate at Clifford Chance turned the legal-tech world upside down when he shared that he vibe-coded a popular legal AI workflow in a matter of hours. Jamie Tso’s post sparked a movement. Suddenly, lawyers building their own tools with AI is all anyone can talk about.

When I attended the Legal Tech Mafia breakfast last week, vibe-coding lawyers were undeniably the main topic of conversation. Despite the moderator’s best efforts to guide us elsewhere, the conversation kept circling back to a spirited debate: Is vibe-coding fundamentally limited — insecure and unreliable, useful for prototypes but too risky for real-world deployment? Or does it represent something more significant? Could it be a genuine shift in how legal software gets built, and perhaps the future of legal tech itself?

As a professional software engineer with 10 years of industry experience, I feel confident claiming that building software with AI is not simply a neat trick for building prototypes, but a true paradigm shift in how software is built. AI coding tools are already shipping production-grade code across the industry despite being brand new.

But aren’t vibe-coded apps brittle and prone to failure? Don’t they break when you push at the edges? How could lawyers ever trust them?

The answer to these questions depends on when you ask. In January of 2026, the answer is yes. Lawyers should not trust apps they vibe-code with their clients’ confidential information unless they have the technical expertise to deploy their tools securely. But if you’re asking one year from now, or in two years, the answer may be very different.

The scale of this shift is so significant, it should call into question every assumption we have about the way software is developed. If we study technological revolutions of similar magnitude from history, we should expect to live in a very different world soon, with new infrastructure and new competencies expected from professionals.

Here’s what the future of the vibe-coding lawyer looks like.

AI is revolutionizing software development

If you had asked me a year ago if I predicted AI would write nearly all of my code by the end of 2025, I’d have told you no way. I wasn’t an AI skeptic — in fact, I would spend hours a day in the Claude chatbot working through problems. I’d already tried AI coding tools like Cursor, and they just weren’t that good. The amount of time it would take me to correct Cursor’s mistakes was more than the amount of time it’d have taken me to write the code myself.

Then Claude Code was released in March 2025 and it changed everything. The first time I saw it autonomously traverse multiple codebases to build a full-stack feature end-to-end without making a mistake, I realized that this was a moment of significance akin to the original release of ChatGPT.

But despite its power, in those very early days of agentic AI coding, there was much debate among coders of whether these tools could ship production-grade software. It still made mistakes. Not everyone knew how to use it well. We still needed a couple more model releases before it could consistently ship high-quality code.

Now, only 10 months later, the conversation is different. The consensus among coders is overwhelmingly that AI coding is the future and that there’s no going back. AI is even improving the code quality of those most skilled in using it. In my case, Claude Code can often diagnose the root cause of a bug much faster than I can, making our codebase more reliable over time.

Practically every new feature or bug fix I ship is now written with Claude Code. Anthropic’s new wildly popular “Cowork” was built completely with Claude Code. Even Linus Torvalds, the famed engineer whose work is regarded as a paragon of rigor and quality among coders, is vibe-coding.

In the words of ChatGPT, “that’s not an incremental improvement. That’s a paradigm shift.”

These examples should call into question the supposition that AI is only capable of building flimsy, insecure prototypes.

The difference between a software engineer building software with AI and a lawyer doing it is that the software engineer has a suite of processes and infrastructure in place that allow them to build confidence in what they’ve built before it’s deployed. Code review, QA testing, deployment pipelines with automated unit tests and security checks, production monitoring, rollback infrastructure, etc. all allow a software engineer to build confidence in what they’ve built before deploying it to production.

The reason why coders have these systems and lawyers don’t is that lawyers have never needed them in the past. But as AI enables more and more lawyers to build their own tools, this is changing.

So can we imagine the legal profession adopting a set of practices that would enable lawyers to reliably and securely build their own tools? I believe we can.

Let’s walk through what secure vibe-coding infrastructure for lawyers could look like in practice.

A lawyer’s job in 2030

You’re an associate lawyer at a law firm in 2030. You’re reviewing a Limited Partnership Agreement for an investor client and need to populate your firm’s standard comments table, a structured summary of the agreement’s key terms. You’ve been using your Legal AI provider’s chatbot to extract the provisions, but it’s laborious to copy and paste the text output back into the table cell-by-cell.

You visit your firm’s tech dashboard and ask if there’s a tool that can automatically extract the key terms and populate the table directly. The answer comes back: no such tool exists.

So you decide to build it yourself.

You click a button that says “build tool.” This opens an interface that allows you to write a prompt to build your application. You describe your problem and the AI agent starts building it.

The agent builds your prototype in a sandboxed testing environment. All of its predefined integrations are mocked-out so that you can immediately begin testing your tool’s functionality as if it’s connected to the real thing.

You test your tool on a set of sample documents. It’s not populating the comments table with quite the right information, so you iterate a few times with the agent until it works precisely.

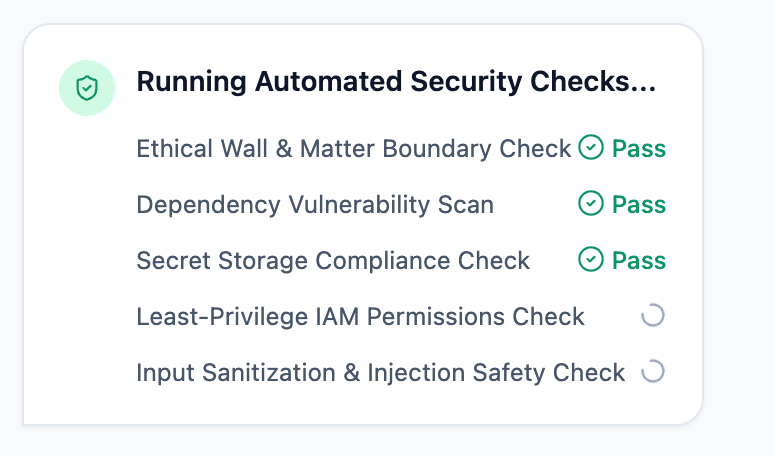

Everything is working as you want it to. You run automated security checks against your tool.

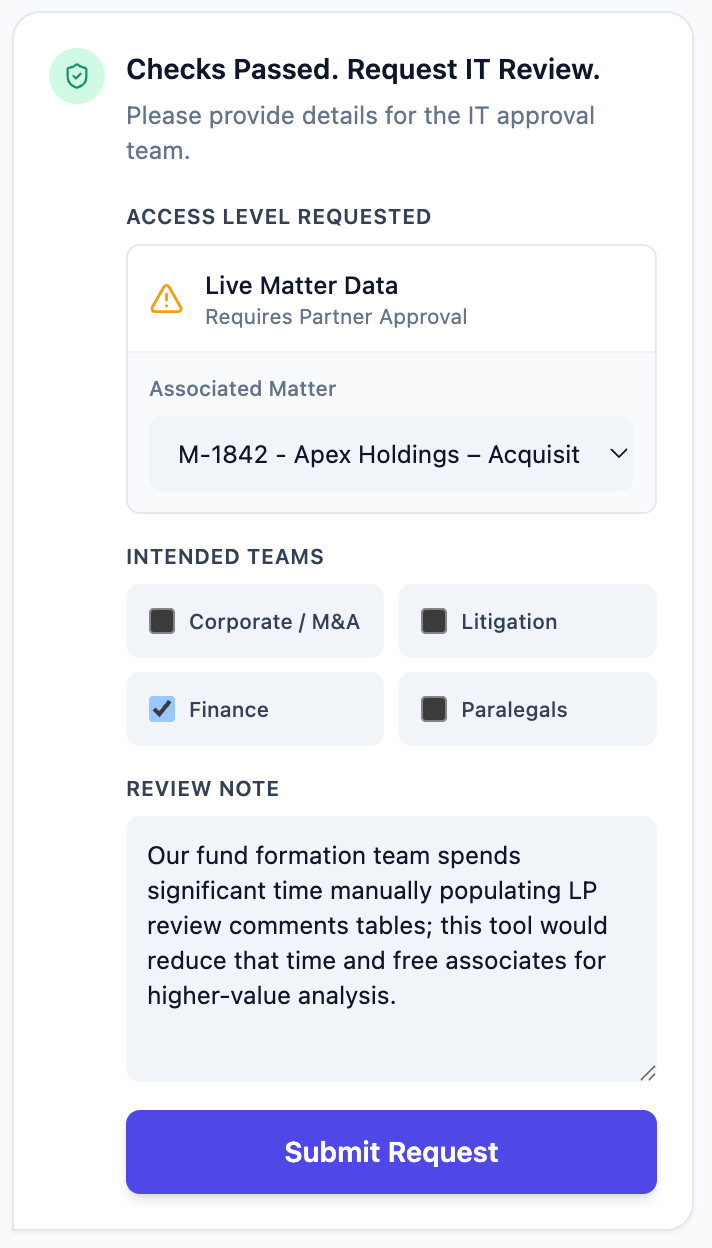

You submit your tool for approval. You describe what it does, who needs access to it, and which matters you need to use it with.

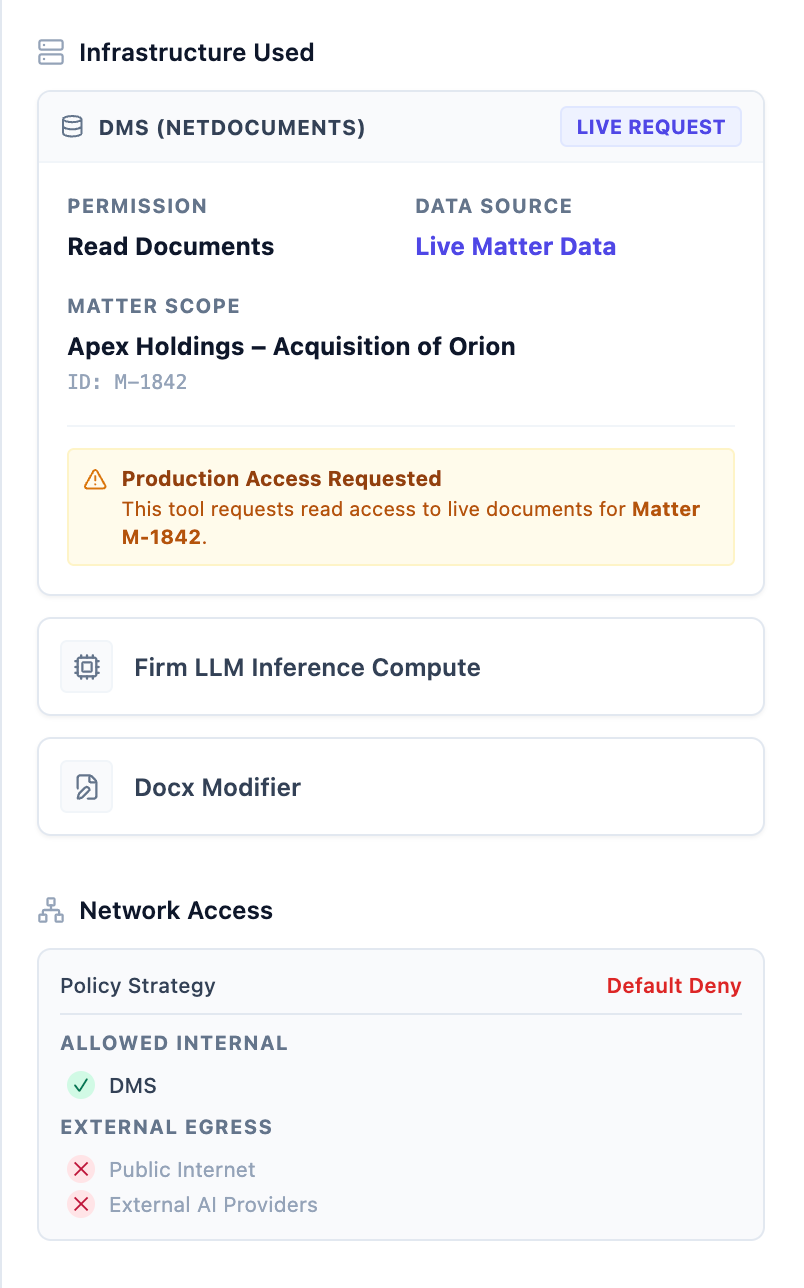

The IT team receives your request and reviews it. They review the tool’s code, the infrastructure components you need access to, the networking permissions it requires, etc. When they approve your tool, a member of the IT team is assigned to be its owner.

After IT approval, your tool is automatically deployed to an isolated container within your firm’s whitelist-restricted subnet. This means it can only communicate with IP addresses explicitly approved by the IT team.

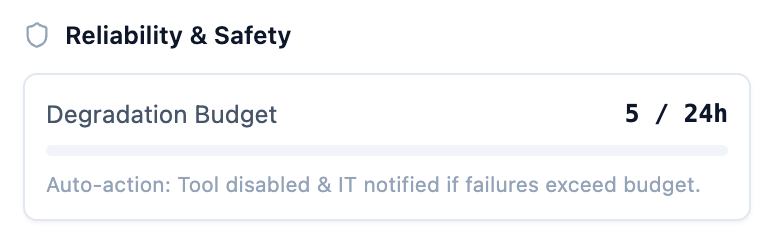

The IT team has allocated a degradation budget of 5 failures for your tool. This means if it fails more than 3 times, it’s automatically taken offline. If the tool ever encounters any kind of issue, a task is automatically assigned to the tool’s owner within the IT team.

Now that your tool is live, the practice innovation team has dashboards to monitor its usage. If it’s popular, they know it’s worth continuing to support and to promote within the firm. If no one uses it, they might choose to discontinue support for the tool.

Over the coming months, your tool becomes very popular amongst associates in the Private Funds team. To reward you and incentivize others to build innovative tools, your firm gives you a bonus.

Legal AI providers aren’t ambitious enough

Consider how this problem would be solved under the current model, where law firms pay legal AI providers small fortunes to build workflows for them.

After you discover the problem, you ask your practice innovation team if you have access to a product to solve it. You don’t, so your practice innovation team makes a feature request to your legal AI provider.

If your legal AI provider decides it’s worth their time, they will add it to their next quarter’s roadmap when one of their employees will vibe-code a solution instead of you. When they eventually deploy the tool (which you didn’t get to test during the development process), the matter you needed the tool for is long over.

Meanwhile your IT team has limited visibility into the development process. They don’t control which teams have access to the tool. They don’t control the network configurations of the container that it runs in. The analytics that the AI provider provides grants them limited, if any, visibility into the tool’s usage within the firm.

Skeptics of AI-coding are concerned that lawyers building their own tools would be insecure. But which of the two development models sounds more secure? The one that gives law firms more control over their tooling, network, and infrastructure or less?

Software development is the new literacy

Prior to the invention of the printing press, literacy was a skill practiced only by specialists and elites. Once the printing press made the written word abundant, literacy eventually became universal.

Prior to the invention of personal computers, typing was delegated to secretaries, who usually had gone to typing school. As computers began to mediate professional work and emails demanded real-time responses, professionals needed to learn to type for themselves.

Prior to the invention of LLMs, software development was practiced only by coders with years of academic training and professional experience. AI coding tools are shattering that constraint.

When technological breakthroughs expand people’s capabilities dramatically, the skills that define professional competence shift. Given how dramatically AI has transformed software development over the past 10 months, I anticipate professional software engineers like myself will no longer be gatekeepers to the development of software in the future.

Instead, individual employees of all types of firms, including law firms, will be empowered to build their own solution when they come across a problem.

This change is already underway. More and more lawyers are building their own tools with AI. I’m a member of a group chat of these lawyers who call themselves “legal quants”, started by Jamie Tso. Every day, the ~50 lawyers in the chat post hundreds of messages sharing the tools they’ve built, the techniques they use to build them, and which open-source libraries are best for legal workflows. These lawyers are true hackers, in the Grahamian sense of the word.

These Legal Quants are paving the frontier of legal tech. One that frees lawyers from being trapped by inadequate tooling. One that empowers them to solve their own problems with agency, and no longer feel beholden to legal tech vendors that don’t understand them. The future of legal tech won’t be built by those vendors. The future of legal tech will be built by lawyers.

Exactly how we should position this topic Jordan - well done!

Wow, this is fantastic! What a brilliant essay and perfectly put into words something I’ve been deeply feeling myself