Why can’t $4.3B in legal AI investment outcompete $20/month for ChatGPT?

And why venture capital disincentivizes building good legal products.

Legal AI startups raised $4.3B in 2025. Every week, a legal AI startup raises a new mega venture capital round. Every week, lawyers lament in r/legaltech that legal AI products aren’t good. Despite being told that AI is revolutionizing the law, many lawyers report these products aren’t reliable enough for them to trust and don’t do much more than ChatGPT. What’s going on?

As the founder of a five-year-old legal tech startup with a product trusted by lawyers across the industry, I’ve developed this belief:

Venture capital-backed AI startups don’t build differentiated products because it’s not part of their strategy.

Venture capitalists and lawyers have conflicting incentives

Venture capitalists (VCs) make money by placing high-risk bets across many startups, expecting that one or two will reach $10B+ valuations. Those winners “return the fund,” covering all the losses from failed investments while generating substantial profits.

The VC business model has capped downside and uncapped upside. At worst, a fund runs out of money, but an early bet on the next Google could return tens or hundreds of billions.

Law firms, on the other hand, have capped upside and uncapped downside. A law firm could close a $50B merger and their total compensation tops out at a negotiated fee. Their downside risk, on the other hand, is unlimited. Sending out the wrong version of a contract for signatures can expose their client to tens or hundreds of millions of dollars of liability. Lawyers are in the business of reducing risk, not taking it.

Additionally, VCs have a short-term incentive to demonstrate quick portfolio gains to their own investors, the limited partners who invest in VC funds. If a VC invests in a startup at a $20M valuation, they want that startup to raise again in 18 months at an $80M valuation so they can use that 4x markup to raise their next fund.

VCs didn’t like legal tech until LLMs

These mismatched incentives have historically made legal tech a bad fit for venture capital. Due to their risk profile, lawyers need to have complete confidence in a product before they adopt it. The product must work reliably, handling every idiosyncratic Microsoft Word formatting requirement across 1000+ page documents, maintain perfect information security practices, and have social proof from other big-name law firms.

Attempts by legal tech companies to play the VC game have historically ended poorly. As a consequence, legal tech developed a negative reputation amongst VCs. When my startup Version Story went through Y Combinator in 2021, a prominent VC advised the legal tech companies in our batch to pivot to a different industry.

The AI gold rush introduced the “Distribution > Product” game to legal tech

This changed when ChatGPT hit the world in fall of 2022. Despite its limited utility at the time, the conventional wisdom among VCs was that AI would automate the practice of law. It was a matter of time before LLMs would do work once done by lawyers. One VC told me, “If you aren’t pitching a plan to automate lawyers, you’re not an AI company.”

But in the early days of ChatGPT, LLMs weren’t yet useful to lawyers. They weren’t smart enough, they hallucinated too much, and the context windows were too small for legal documents. VCs observed the models were rapidly improving, however, and their Twitter feeds offered frequent reminders artificial general intelligence was on the way. GPT-4 couldn’t automate legal reasoning, but GPT-7 might.

An idea emerged that finally made the legal market palatable to VCs. Whichever startup captured the most market share by the time AI became capable of replacing lawyers would usher in the legal AI revolution — transforming a $1T legal services industry and defining how law is practiced with AI at the helm.

And with that idea, a new set of startups entered the scene seeking to capitalize on a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

How to scale distribution with an undifferentiated product

The conventional wisdom in the startup world is to build a great product and let distribution follow naturally. YCombinator’s motto is “Build Something People Want” and their entire startup curriculum is oriented around that idea.

But becoming the industry leader before AI is capable of high-quality legal reasoning requires capturing distribution before the product is useful. A friend of mine who founded a legal AI startup works from the office of his startup’s VC backer. Written atop the whiteboard on their wall are the words “Distribution > Product”.

Here’s how to capture distribution without a differentiated product:

Step 1) Sell fear, not solutions

Legal AI startups want lawyers to fear AI. They want them to believe that the AI revolution threatens their livelihood. Some of their marketing strategies are oriented around it. A video on the homepage of a leading AI company begins with the line:

“Being up to date is not that difficult. But becoming obsolete is really easy.”

Recall that lawyers are incentivized to eliminate risk. If they believe there’s a chance AI could disrupt the legal industry, that’s a risk to be managed. From the law firm’s perspective, a legal AI subscription is a strategy to minimize risk. If an AI revolution is coming, the firms best equipped to manage the transition will be the ones that have already integrated with the leading legal AI provider.

Step 2) Charge exorbitant prices

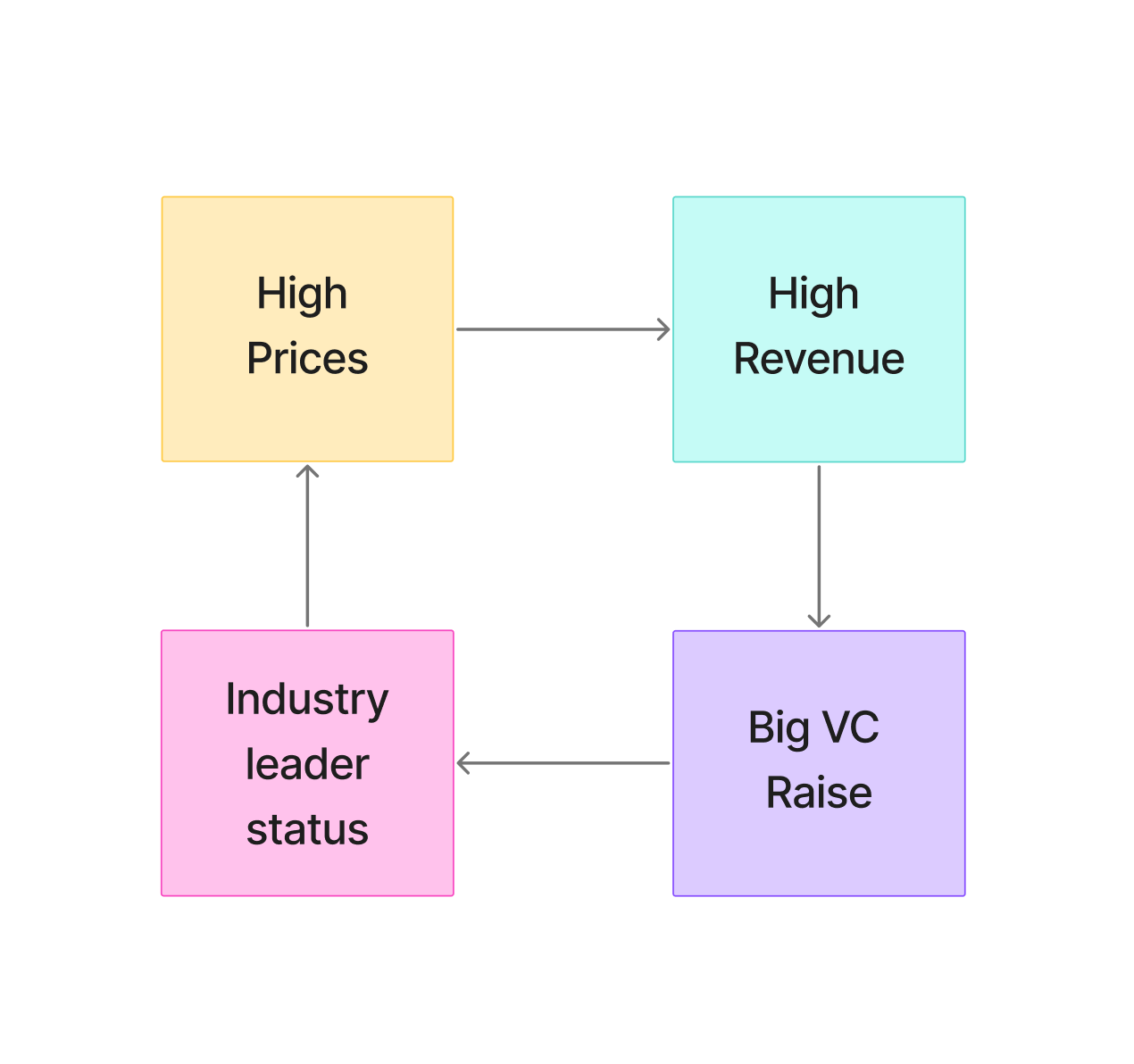

Because the AI companies sell insurance for disruption, they command far higher prices than traditional legal tech products. This creates a high top-line revenue figure to show VCs, allowing them to raise more money and further cement their position as the industry leader. As their status grows, they win more customers, increase their pricing power and ability to raise more money.

Why would a firm pay high prices for a leading legal AI provider when many other startups provide similar offerings at lower prices? Because the leading AI provider mitigates the most risk.1 This could be a pragmatic strategy from the law-firm’s perspective. If AI disrupts the legal industry, subscribing to the industry-standard legal AI vendor guarantees that you will be in the same boat as your competitors. Law firms don’t know which of the other boats will sink and which will pull ahead, and law firms aren’t in the business of making bets.

Step 3) Bet on OpenAI improving their models

Legal AI startups do not build AI. Research labs like OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind build AI. These labs pioneer AI research and release large language models (LLMs) for consumers to use via chatbots and companies to integrate with via APIs. Legal AI startups build products on top of these models.2

The products that legal AI startups build on top of the models are of secondary importance for many of their strategies. In the initial phase of the AI era, many of these companies found they could showcase the foundation model’s improvements, and thereby foster the impression that they were innovating.

Will “distribution > product” work in legal? Probably not for much longer.

If recent discussions in r/legaltech are a bellwether, however, this strategy might be near the end of its life.

When asked what their product can do that ChatGPT can’t in a recent AMA, a legal AI founder replied that their product could:

Extract data from +10.000s documents

Create workflows that redline contracts according to firm-specific playbooks

Draft contracts while keeping formatting in Word

Leverage precedent and internal knowledge basis as context

etc.

Later that same week, a lawyer used AI to create his own Word add-in. Another used Gemini studio to vibe-code a tool for bulk document analysis. “Workflows” built on top of AI offer less of a technological moat when a lawyer without an engineering background can use AI-coding tools to build them in an evening. As communities like this grow, more lawyers and law firms will discover they can access the power of AI models directly and cut out the middlemen, thereby saving considerable amounts of money.

If these trends continue, we will likely see a different type of strategy win in legal tech. To differentiate themselves in the age of AI, products must solve hard technical problems that can’t be vibe-coded. Building great products that lawyers love on a strong technical foundation seems like a more durable strategy.

This is why we’ve spent years at Version Story building critical document processing infrastructure to solve legal version control. It’s why we manually worked through thousands of edge cases to ensure that our document comparison and merge technology works across every possible permutation of Microsoft Word formatting options. And it’s why we’re excited for a future where AI puts more power in lawyers’ hands while the companies they partner with deliver value that AI alone can’t.

This is my conjecture based on facts on the ground. There is plenty of evidence from product reviews and demos supporting the premise that users feel that big-name legal AI products are undifferentiated. Given that, the alternative hypothesis explaining law firms’ willingness to pay high prices is that big-name AI startups just give better demos. Maybe, but I suspect my hypothesis is more likely to be the determinative factor.

Some legal AI startups do “fine-tune” the foundation models by training them on additional legal documents. But these gains are marginal. Each time OpenAI or Anthropic releases a new model, it leapfrogs whatever improvements the legal AI companies achieved through fine-tuning the previous one.

Great analysis. I think this even applies to AI companies outside the legal tech space too. I’m keeping my eye on these companies.

Good stuff, Jordan. We featured you guys in our just launched personal injury newsletter: https://newsletter.rankings.io/p/airlines-face-new-scrutiny-over-toxic